The Evolution of Cardiovascular Anatomy in Vertebrates

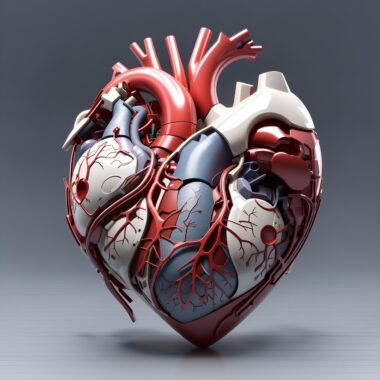

The cardiovascular system in vertebrates has undergone significant evolutionary changes, adapting to various environments and lifestyles. Initially, early vertebrates exhibited a simple two-chambered heart, which efficiently supported their low metabolic demands. As species evolved, the complexity of the heart increased to ensure higher efficiency in blood circulation. Most notably, fish possess a two-chambered heart with atrium and ventricle, while amphibians transitioned to a three-chambered heart for better oxygenation. This transition marked an essential step toward the evolution of more sophisticated circulatory systems. In reptiles, the heart further evolved into a more advanced structure, characterized by partially divided ventricles, allowing for more effective separation of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood. This anatomical change enabled reptiles to thrive in terrestrial habitats. Birds and mammals, on the other hand, exhibit a fully four-chambered heart, providing high levels of oxygen delivery and supporting their high metabolic rates. These adaptations illustrate the remarkable complexity and efficiency that characterize the vertebrate cardiovascular system, demonstrating how anatomical evolution is deeply intertwined with environmental adaptations and the physiological demands of different species.

The role of the cardiovascular system extends beyond mere oxygen transportation; it plays a pivotal role in regulating body temperature and immune responses. In endothermic vertebrates such as birds and mammals, the efficient delivery of oxygen and nutrients is crucial for maintaining a stable internal environment. These animals have developed advanced vascular networks, assisting in thermoregulation. For instance, the presence of counter-current heat exchangers in birds’ legs minimizes heat loss, while large surface areas in capillaries facilitate nutrient exchange. Furthermore, blood also transports hormones and other signaling molecules throughout the body, contributing to homeostasis. Different vertebrate groups have also developed specific adaptations in their blood components, such as red blood cell types and plasma proteins, enhancing oxygen transport efficiency. In marine mammals, specialized hemoglobin variants ensure adequate oxygen storage during dives. Understanding these anatomical adaptations helps in uncovering the evolutionary pressures that shaped vertebrate cardiovascular systems. Researchers have employed comparative studies across various taxa, utilizing fossil evidence and modern technologies to reveal the intricacies of cardiovascular evolution. Thus, cardiovascular anatomy not only tells a story of survival but also highlights the dynamism of evolutionary processes.

Comparative Anatomy of Vertebrate Hearts

The comparative anatomy of vertebrate hearts showcases remarkable adaptations among different species inhabiting diverse environments. The heart structure directly reflects an organism’s lifestyle, metabolic needs, and evolutionary lineage. For example, the heart of a fish functions efficiently in aquatic environments, pushing blood in a single circuit through gills before entering the systemic circulation. Conversely, the three-chambered hearts found in amphibians are designed to accommodate their dual lifestyles in water and on land. This heart structure provides a compromise, effectively separating pulmonary and systemic circuits, albeit incompletely. Reptiles exhibit further refinement, with a partially divided ventricle enabling some degree of separation between oxygenated and deoxygenated blood. Birds and mammals represent the evolutionary pinnacle in cardiovascular anatomy, possessing fully septated hearts. This four-chambered structure is essential for supporting their high metabolic demands, ensuring efficient oxygenation of blood. Additionally, birds have developed unique adaptations such as a muscular, hypertrophied heart with a high rate of contraction. These heart structures not only indicate evolutionary advancements but also provide insights into the ecological niches occupied by each vertebrate group, emphasizing the connections between anatomy, physiology, and evolutionary history.

The evolution of cardiovascular anatomy in vertebrates also leads to remarkable variations in blood vessels. Arterial and venous systems have adapted to the metabolic demands imposed by different habitats. In fish, arteries transport deoxygenated blood from the heart directly to the gills, where gas exchange occurs before returning to the body. Amphibians possess a more complex arrangement, with pulmonary arteries transporting blood to the lungs for oxygenation before it enters the systemic circulation. The emergence of a double circulatory system in reptiles further reflects adaptive changes, as this structure allows them to efficiently use oxygen for terrestrial life. In mammals and birds, the arterial systems further diversify, with specialized vessels providing the necessary blood flow to various organs. For instance, the coronary arteries supply the heart itself, while the carotid arteries deliver oxygen-rich blood to the head. Similarly, different venous systems exist to transport deoxygenated blood back to the heart. These vascular adaptations illustrate the intricate relationship between anatomical evolution and environmental challenges faced by various vertebrate lineages, revealing how species have evolved sophisticated solutions to survive and thrive.

Adaptation and Evolutionary Pressures

Adaptation and evolutionary pressures play a crucial role in the development of cardiovascular anatomy. Environmental changes, such as shifts in climate, habitat availability, and predation pressures, have influenced vertebrate evolution across millennia. For instance, early terrestrial vertebrates had to establish mechanisms to efficiently supply oxygen to their tissues as they moved from aquatic to terrestrial environments. This transition demanded significant anatomical changes, leading to improved heart structures and vascular networks. The evolution of a four-chambered heart in birds and mammals represents a response to the increased metabolic needs of active lifestyles. Endothermic characteristics driven by ecological demands prompted further specialization, including adaptive features such as the heart’s size and muscularity. Selection pressures dictated the efficiency with which the cardiovascular system operates, ensuring that each species could effectively manage oxygen intake and waste removal. Research into fossilized cardiovascular structures has revealed insights into how ancient vertebrates adapted to their environments. The comparative approach within evolutionary biology acknowledges these changes and provides vital understanding regarding how different vertebrate groups converged upon similar anatomical solutions in their respective evolutionary journeys.

In addition to structural changes, the evolution of cardiovascular anatomy also encompasses variations in heart function across vertebrates. Specific adaptations can enhance the heart’s pumping efficiency, ensuring that blood circulation meets the physiological requirements unique to each species. For example, the heart rate of small mammals and birds tends to be higher to support their energetic lifestyles. Conversely, larger animals such as elephants exhibit much slower heart rates, compensating for their size and metabolic efficiency. This divergence in heart function highlights the necessity of variability within the cardiovascular systems that mirror each species’ ecological adaptations. Additionally, the impact of social behaviors, such as flocking or herding, influences cardiovascular requirements, establishing compelling links between environmental interactions and anatomy. The mammalian heart’s electrical conduction system, with specialized nodes and pathways, allows for sophisticated regulation of heartbeat, demonstrating a further degree of adaptation. Such functional variability signifies the dynamic interplay of evolution and physiology, underpinning the cardiovascular system’s vital role across diverse vertebrate species. This research underscores the importance of integrating ecological contexts when exploring the evolutionary trajectory of animal anatomy.

Future Directions in Cardiovascular Research

Looking ahead, future directions in cardiovascular research promise to unravel further complexities in vertebrate anatomy. Advancements in technologies such as imaging techniques, genetic manipulation, and computational modeling are leading to novel insights into cardiovascular systems. Researchers can now visualize cardiac structures in unprecedented detail, allowing for a deeper understanding of evolutionary relationships. Moreover, genomic studies are shedding light on the molecular mechanisms that drive the development of different cardiovascular adaptations among vertebrate groups. Insights gained from studying extremophiles or endangered species can inform conservation efforts, highlighting cardiovascular vulnerability to environmental changes. The exploration of cardiovascular anatomy can also extend into biomechanics, analyzing how blood flow dynamics relate to heart structure and performance across species. Collaboration between fields like paleontology and evolutionary biology fosters a richer understanding of cardiovascular evolution, offering clues about past adaptations and future trends. Additionally, implications for human health are profound, drawing parallels between vertebrate cardiovascular evolution and understanding cardiovascular diseases. As research progresses, the evolutionary narrative of vertebrate cardiovascular anatomy continues to reveal enduring themes of adaptation, resilience, and the ceaseless interplay between form and function.

The study of cardiovascular anatomy in vertebrates provides essential insights into evolutionary biology and offers lessons that may apply beyond the animal kingdom. The understanding of how various species have adapted their cardiovascular systems informs broader ecological and physiological principles. Cardiovascular evolution exemplifies how life on Earth has diverse solutions to meet similar challenges. Integrating findings from comparative anatomy into conservation biology is increasingly important as human activities put widespread pressure on biodiversity. Understanding cardiovascular adaptations can aid wildlife conservation strategies by ensuring that protected species have suitable habitats that support their unique physiological needs. Furthermore, cardiovascular anatomy research could inform fields such as regenerative medicine, potentially leading to novel treatments for heart disease. By studying evolutionary adaptations in vertebrate hearts and blood vessels, scientists could uncover mechanisms that result in improved healing and recovery processes. The lessons gleaned from vertebrate cardiovascular evolution reinforce the idea of interconnectedness in life sciences, emphasizing how biological processes are shaped by evolutionary history and environmental context. The continuous exploration of this field serves not only to enhance our knowledge of vertebrate physiology but also to address pressing challenges in health and conservation.